And yet there are wonderful art writers who are also consummate storytellers. Too much writerly attention to the form of a text can lead to dismissive charges of belle-lettrism. Art writing, as pluralistic and uneven as the genre may be, is tightly linked to an established set of references and intellectual expectations (not to mention such crucial, if mundane, practicalities as word counts, formats, venues, deadlines and fees). Some accounts insist that the function of art criticism, its injunction to critique, takes precedence over any creative exploration into the gulf that separates the moment we see an art work from the moment we are able to say something meaningful about it. Most discussions about art writing today, especially those that worry about the role of the critic or the state of criticism, tend to centre on its historical relationship to the discipline of art history and to the vagaries of the art market, or on more philosophical questions of aesthetic judgment.

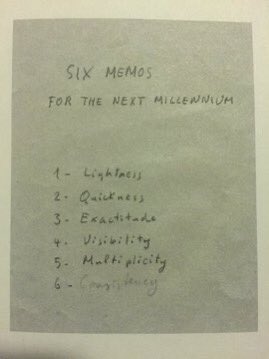

Italo calvino quickness how to#

And they must negotiate how to filter their subjective experience into or out of their rendering. In order to communicate meaning, art writers, like translators, must navigate the familiar if treacherous straits of fidelity to, and betrayal of, pre-existing objects and discourses. I mean nothing pejorative by that distinction: translators generously lend themselves to texts and to authors, just as art writers lend themselves to art and to artists. Because our texts depend on the aesthetic imagination and artistic production of others, we are perhaps more akin to translators than we are to ‘true’ writers. This (wholly generic) fantasy is hospitable enough to art writers – a somewhat special breed. I always imagine that these writers have collections of talismans – favourite songs, images, texts or careworn mementos – that surround the workspace or are ritually tucked away and retrieved when required. These companions, summoned into what Marguerite Duras once termed the writer’s ‘necessary solitude’, can serve as a comfort or a distraction. I have always imagined that ‘creative’ writers confront the blank page accompanied by a coterie of kindred spirits – authors, fictional characters, fantastical creatures or historical figures – with whom they identify or against whom their own imaginations have been shaped.

Italo Calvino at his home in Paris, 1984.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)